Cross-Examination: Unconscious Decisions – Who Should Be Able to Say Yes to Clinical Trials?

Content Contributor, Jade du Preez

Academics and Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) have raised concerns over upholding consumer rights where clinical trials have been conducted on unconscious patients. What is in the best interests of the patient who cannot consent? The question is complex, and it is one that reasonable people may disagree on. However, the present relevant passage in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers' Rights may allow for an interpretation that is either too prohibitive, so as to be ignored, or too permissive, so as to be irrelevant. In a paper published earlier this year, Associate Professor Joanna Manning argued that the scope of that disagreement would be best dealt with by an answer in legislative reform. The need for transparency has been long called for by the Auckland Womens’ Health Council. In particular, representatives have been advocating for a strengthening of consumer rights in respect of clinical trials that pose no benefit to patients or the wider public. This issue is compounded by legislative changes that have weakened the ability of ethics committees to review certain treatments, a reversion that has been criticised as taking the health system back to a time before the Cartwright Inquiry.[1]

The current situation

To begin, it may help to break down some of the categories of treatment that can be applied in clinical trials:

- There may be those that may provide direct assistance to the patient concerned, or therapeutic treatment.

- There are those that might indirectly assist the patient if he or she is a member of a population that benefits from advancements in research. The size of that population – e.g. sufferers of a particular heart condition, or residents of a nation – may in turn lead us to different conclusions as to whether the benefit can be said to be enjoyed by that particular patient. Also, in this latter category we may consider the particular issue of non-inferiority trials.

Non-inferiority trials, the subject of controversial testing in 2014[2], are described as an assessment of whether a new experimental treatment is “not unacceptably less efficacious than the current standard.”[3] This research, motivated by an interest to confirm that a drug is as good as another on the market, may then be primarily serving the interests of a biotechnology company rather than the recipient patient. Without parameters or definition regarding what constitutes the best interests of a patient, a simple argument that market competition for pharmaceuticals is of benefit to society could be used as a basis to trial without consent. Lynda Williams of the Auckland Women’s Council cautions: “there is big money involved in clinical trials and both the investigators and the DHBs have a huge conflict of interest in deciding what research is lawful and what is not.”

Should it happen at all when patients are unable to consent?

Where research without consent (RWC) occurs, it is generally followed by retrospective consent being sought from the affected patient. To some this is unacceptable. Professor Gareth Jones of the University of Otago’s Bioethics Centre commented:

“The notion of ‘retrospective consent’ is at odds with that of ‘informed consent’. Retrospective consent is not informed, and it should not be made to appear as though it is. Even if the patient consents after the event, they have been placed in an untenable position, since they are not able to do otherwise…Retrospective consent also sets a dangerous precedent, since once normalized, it will legitimize a whole raft of other cases that may bear little resemblance to the current antibiotics research.”[4]

Though the notion of experimental treatment administered to an unconscious patient may feel wrong, it is not categorically considered unacceptable. RWC is currently permissible in certain situations under specific conditions in the US, EU member states, Canada, and Australasia.[5] Those certain situations and specific conditions are what need attention; the devil is in the details. Unfortunately New Zealand legislation is rather more bedevilled by an absence of details.

International instruments provide some guidance on the limited circumstances when such research may be justified.[6] The World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki is considered the cornerstone of human research ethics and where the consent of unconscious patients is concerned, section 29 provides:

[x_blockquote type="left"]Research involving subjects who are physically or mentally incapable of giving consent, for example, unconscious patients, may be done only if the physical or mental condition that prevents giving informed consent is a necessary characteristic of the research population. In such circumstances the physician should seek informed consent from the legally authorized representative. If no such representative is available and if the research cannot be delayed, the study may proceed without informed consent provided that the specific reasons for involving subjects with a condition that renders them unable to give informed consent have been stated in the research protocol and the study has been approved by a research ethics committee. Consent to remain in the research should be obtained as soon as possible from the subject or a legally authorized representative.[/x_blockquote]

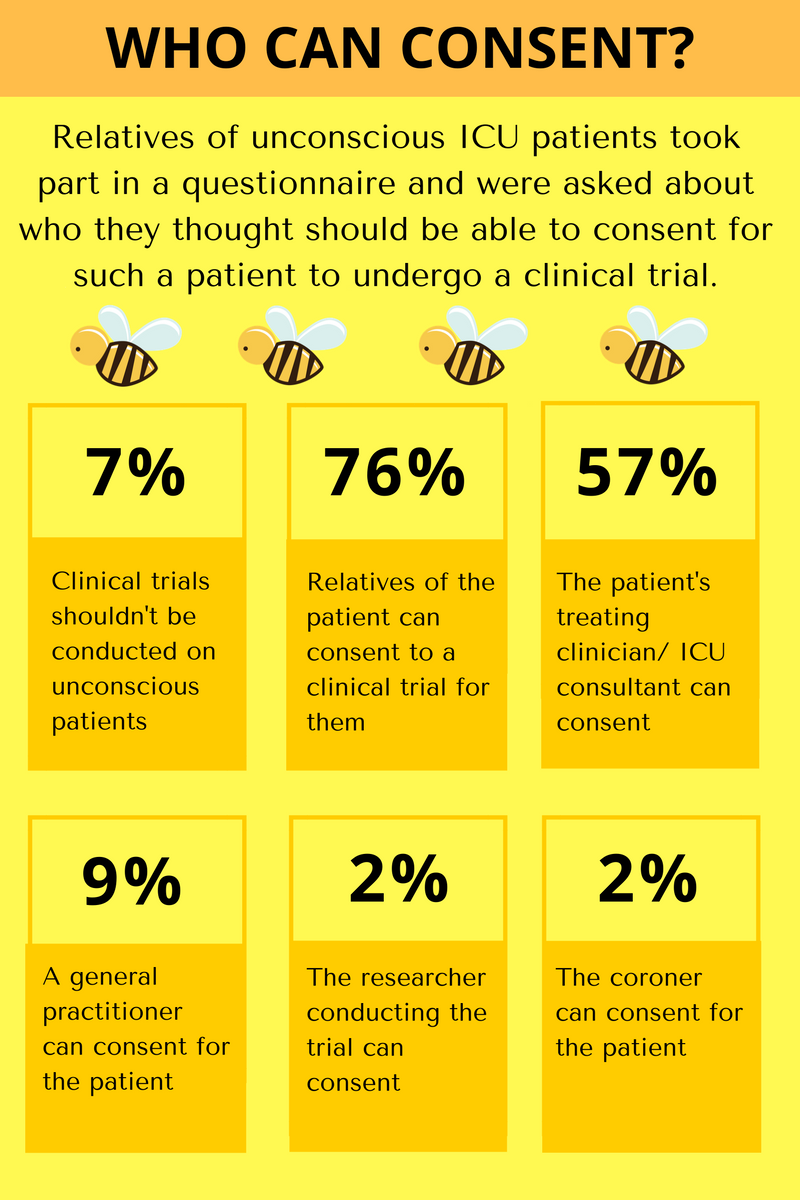

This qualification highlights the importance of perspectives from outside the health system, including legally authorised persons – often family members – and those on ethics committees. Though research has indicated some evidence to the contrary, family members may be those best positioned to reflect the preferences of an unconscious patient. Where such a representative is unavailable, ethics committees provide an important role in their prior assessment of when a particular treatment would likely be in the best interests of a patient.

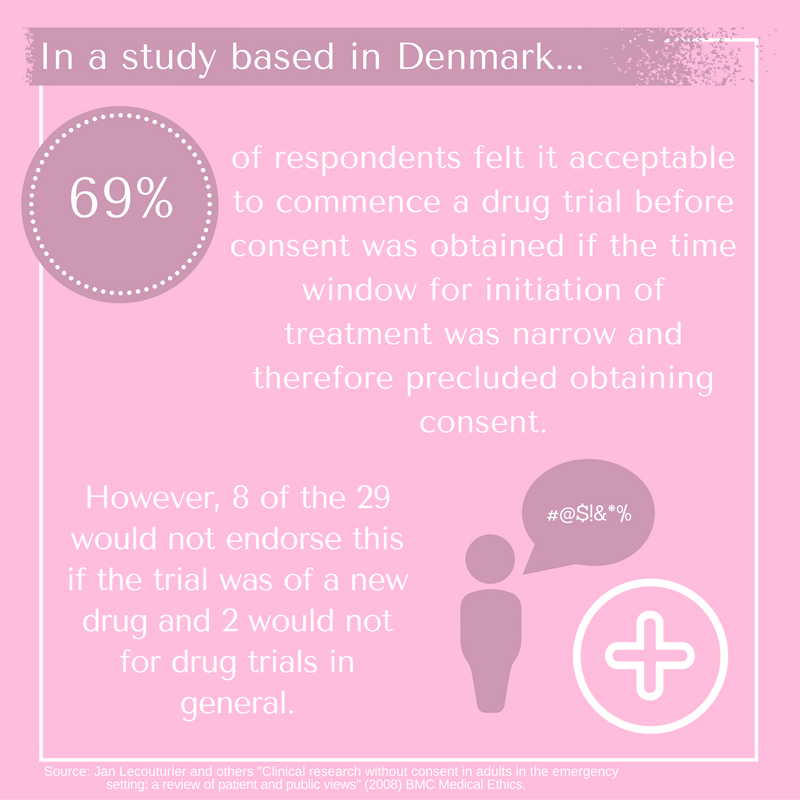

Generally, it is family members who would provide consent on behalf of an unconscious patient in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). International research has revealed considerable variety in public views on this matter.[7] Consent rates by relatives when ICU patients are included in large interventional trials vary from 58 to 96%.[8] Details of studies are varied, as are the nature of trials on patients involved. However, this should at least signal the importance of a cautious approach in making blanket assumptions as to a view on the best interests of a patient and the degree of consent likely to be obtained. By way of example, in research concerning consent given by family members in Denmark, the following was found:

“Twenty-nine of the 42 respondents felt it acceptable to commence a drug trial before consent was obtained if the time window for initiation of treatment was narrow and therefore precluded obtaining consent. However 8 of the 29 would not endorse this if the trial was of a new drug and 2 would not for drug trials in general.”[9]

These shifts based on the content of a study highlight how different information may be regarded as important by the public and guide when a trial is appropriate. If anything, this indicates that scrutiny and a case-by-case assessment is what would best reflect the public interest.

The Law in New Zealand

As a starting point, section 10 of the Bill of Rights Act states that “every person has the right not to be subjected to medical or scientific experimentation without that person's consent.”[10] This is qualified under s 18(1)(f) of the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, in which a welfare guardian may only consent to an incompetent person’s participation in research when the purpose is saving that person’s life or of preventing serious damage to that person’s health.[11] In the absence of a welfare guardian, the Code of Conduct Rules apply. The focus of debate has been 7(4)(a):

Right to make an informed choice and give informed consent

(4) Where a consumer is not competent to make an informed choice and give informed consent, and no person entitled to consent on behalf of the consumer is available, the provider may provide services where—

(a) it is in the best interests of the consumer; and

(b) reasonable steps have been taken to ascertain the views of the consumer; and

(c) either,—

(i) if the consumer’s views have been ascertained, and having regard to those views, the provider believes, on reasonable grounds, that the provision of the services is consistent with the informed choice the consumer would make if he or she were competent; or

(ii) if the consumer’s views have not been ascertained, the provider takes into account the views of other suitable persons who are interested in the welfare of the consumer and available to advise the provider.

The area relied on is “in the best interests of the consumer”. These few words can have wildly different meanings depending on one’s philosophical standpoint. It may feel intuitively safe to assume the trial of a treatment known to be as good as, but possibly better than, standard treatment would be in the best interests of a patient. However, this will have exceptions; a Jehovah’s Witness patient wishing to refuse a blood transfusion is one such scenario. Nonetheless, this therapeutic administration of treatment may sit more easily with conceptions of a patient’s “best interests”. It becomes more complicated when administration of treatment in research will not harm the patient but will benefit the wider public, and / or others suffering similar injury. Does that still qualify as in the patient’s best interests?

Professor Grant Gillet of Otago University argues that clinical trials should generally proceed in situations where experimental treatment is found to be at least equivalent to existing treatment. His argument is that it should be a matter of indifference from the patient’s perspective as to whether the existing standard treatment or the potentially more beneficial treatment is administered. He proposes that it is broadly in the patient’s best interests that the medical profession progress with research that benefits society generally:

[x_blockquote type="left"]“It would be in accordance with good care and the best interests of patients, more broadly conceived, for people to want to contribute to medical knowledge in conditions of uncertainty. This is almost self-evident because it is always good for a health care system to be extending and using knowledge about the patient and his problem and there are real benefits to a patient in being cared for by a medical system in which active clinical research is going”[/x_blockquote]

He suggests that is only in certain extreme situations that a patient would refuse treatment beneficial to health and that it should be assumed that we all have some altruism which should be encouraged.[12] This degree of assumption may be out of step with public opinion and the way that subtle differences influence our perception of what constitutes appropriate treatment. Legally-speaking, further safeguards seem wise. Earlier this year, Joanna Manning of Auckland University wrote an article advocating for law reform which highlighted issues with the current code of rights.

“Right 7(4) immediately rules out participation in Phase I trials, which are of no benefit to the subject. It probably also does so for Phase II and III randomised controlled trials. If the investigator thinks that there is a good prospect that the intervention will be of direct benefit to the subjects receiving it, it may be able to be said that participation is in their best interests. But the subject may be allocated to the standard treatment or placebo arm, for whom that could not then be said. Since it is not known which group will end up receiving the best treatment, it is not possible to say that participation in the research is in each and every participant’s best interests… and so Right 7(4), if faithfully applied, is incapable of being satisfied.”

Professor Manning suggests that New Zealand should follow international legislative examples providing for research to be carried out while ensuring “comprehensive, detailed and strict protections” for patients. Her recommendations include:

- Mandatory approval by an ethics committee with advice on possible clinical, ethical, and psychosocial problems of research;

- Individuals who lack capacity should not be used where competent subjects may be recruited;

- Efforts should be made to obtain the prior consent from the participant, and any statement or other evidence that the participant does not wish to participate should be taken seriously;

- The person’s legal representative has either given informed consent to, or a consultee has not vetoed the subject’s participation and either party can withdraw the participant from the trial at any time without detriment;

- Where the participant regains capacity, the participant should be informed of his/her inclusion in the research and of the option to withdraw his/her data from it without any reduction in quality of care as soon as reasonably possible;

- The research should be likely to either benefit the patient, or other members of the group to which the patient belongs, and the research entails only minimal risk and burden if any;

- Financial inducements should not be allowed.[13]

These elements provide a greater role for the patient’s wishes, the legal representative or family member and ethics committees. However, these too may require further attention before possible implementation.

The Role of Ethics Committees

Ethics committees have been regarded as an important space for involving public input and ensuring transparency in situations of clinical research. This interest in participation is not limited to New Zealand; international studies have strongly indicated a similar sense of concern that there is involvement of the community in assessing the appropriateness of in the sphere of a highly controversial area of bioethics.[14] In recent years, legislative changes have considerably altered the composition of ethics committees, arguably to the detriment of lay person involvement in consultation. The Auckland Women’s Council described the issue as follows:

Prior to the [legislative]changes introduced in 2012 ethics committee chairpersons wanted greater protections for those enrolled in trials sponsored by international pharmaceutical companies; now they have deadlines that must be met, and enabling researchers to get those patients enrolled one way or another is the priority.[15]

As a result of changes, critics have raised concern over the impacts on review of trials and public participation. Charlotte Paul, former head of the Preventive and Social Medicine department at the University of Otago, member of National Ethics Advisory Committee (NEAC), and medical adviser to the Cartwright Inquiry flagged the following issue:

“Some clinical trials will therefore receive only expedited review. This was not recommended by NEAC in 2009 because clinical trials, compared with observational studies, entail an intervention and hence more potential for harm. Indeed, the committee recommended "close ethical scrutiny" for trials.”[16]

We may consider that this is another strand of the problem requiring legislative attention to ensure that efficiency doesn’t override democracy where health is concerned.

Where to next?

Provided guidance from international research on public concerns, and a review of sound practice internationally, it follows that serious consideration and discussion over the content of comprehensive legislation would be beneficial. Further, to give voice to concerns when research may be over-stepping the mark, ethics committees need to be enabled to properly review proposed clinical trials. The question of what is in our best interests is far too broad to be left without qualification; it’s a philosopher’s field day. To begin we might simply ask: if it were you or I without the ability to speak for ourselves, whose voices we would have represent us?

–

The views expressed in the posts and comments of this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the Equal Justice Project. They should be understood as the personal opinions of the author. No information on this blog will be understood as official. The Equal Justice Project makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. The Equal Justice Project will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information nor for the availability of this information.

[1] “Auckland DHB to go ahead with trial” Radio New Zealand (online ed, New Zealand, 14 May 2014).

[2] Martin Johnston “Drugs tested on critically ill, coma patients” New Zealand Herald (online ed, Auckland, 14 May 2014).

[3] Seokyung Hahn "Understanding noninferiority trials" (2012) 55 Korean J Pediatr 403.

[4] "Medical ethics and unconscious patients – experts respond" (14 May 2014) <www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz>.

[5] Jan Lecouturier and others "Clinical research without consent in adults in the emergency setting: a review of patient and public views" (2008) BMC Medical Ethics.

[6] Above, n4.

[7] Above, n5.

[8] Anders Perner and others "Attitudes to drug trials among relatives of unconscious intensive care patients" (2010) BMC Anesthesiology.

[9] Above, n8

[10] New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, s 10.

[11] Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988.

[12] G. R. Gillett "Intensive care unit research ethics and trials on unconscious patients" (2015) 43 Anaesth Intensive Care 309.

[13] Joanna Manning “Non-Consensual Clinical Research in New Zealand: Law Reform Urgently Needed“ (2016) 23 JLM 516.

[14] Above, n5.

[15] “Enrolling Unconscious Patients In Clinical Trials” (May 2014) <www.womenshealthcouncil.org.nz>.

[16] Charlotte Paul “Research participants need protection” Otago Daily Times (online ed, Otago 12 October 2011).