Domestic Violence Victims’ Protection Act - a great leap forward?

Amy Dresser

The Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018 is an Act “for every victim of domestic violence who ever felt trapped and for every person who knew a workmate was being abused but did not know how to help.”[1] New Zealand has the highest prevalence of domestic violence of any country in the OECD,[2] and the police attend a domestic violence call every five and a half minutes.[3] Clearly, there is a problem. The new Act establishes flexible working hours, leave and freedom from discrimination for people affected by domestic violence. It is not a solution for domestic violence, but is it the first step to ending the cycle? I will discuss the promise and pitfalls of the new Act, including its role in the broader domestic violence framework, its application for domestic violence survivors, and the costs for employers.

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is best understood as a pattern of harm, rather than a series of incidents affecting an individual.[4] Psychological control is a key component, and domestic violence is entangled with intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect.[5] James Ptacek characterises intimate partner violence as “social entrapment”, which identifies three central issues: the survivor’s social isolation due to the perpetrator’s coercive control, the indifference of institutions toward their suffering and compounded structural inequities such as gender, race and class.[6] Domestic violence is a multi-layered issue, and the Act seeks to tackle the first two aspects of social entrapment by removing a layer of isolation for those who work, and making it impossible for an employer to be indifferent. The structural aspects of domestic violence must also be acknowledged, as almost half of all domestic violence deaths occur in the most deprived neighbourhoods and Māori are five times more likely to be offenders and four times more likely to be victims of domestic violence deaths than non-Māori.[7]

Survivors of domestic violence are often undermined for not leaving violent relationships, but there are two central issues with this idea. First, the onus should be on the perpetrator to stop the harm rather than the survivor to escape the harm.[8] Secondly, the coercive control over survivors of domestic violence makes it difficult for them to escape violent relationships due to limited resources and places of sanctuary.[9] Jan Logie comments that “domestic violence is not just in the home, it is between the people … wherever the victim goes, the violence will follow".[10] However, there is correlation between a survivor’s ability to escape a violent relationship and their financial independence.[11] The ability for someone affected by domestic violence to hold onto their job due to paid leave or flexible hours (plus the support of their employer) could be momentous in escaping or quelling domestic violence.

The Act

Jan Logie, Green Party MP, introduced Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Bill as a member’s bill on International Women’s Day last year, and it passed its third reading on 25 July 2018 (without the support of the National Party). The Act amends the Employment Relations Act 2000, the Holidays Act 2003 and the Human Rights Act 1993.

The Act entitles an employee affected by domestic violence to request short-term flexible work arrangements and entitles the employee to ten days’ domestic violence leave within a twelve-month period, to be paid out by the employer.[12] The employer may request proof of domestic violence (although the Act does not prescribe which form the proof must take) and may deny flexible working arrangements if it cannot be reasonably accommodated.[13] The Act also amends discrimination law to make it unlawful for an employer to treat an employee adversely if they believe the employee is affected by domestic violence.[14]

Last year the Equal Justice Project made a submission on the bill. The submission recommended more clarity over the requirements for denying requests for flexible work and documentation of domestic violence.[15] These were not implemented, and a hole remains in the Act over what constitutes “proof” of domestic violence. The submission also noted that the costs for businesses implementing domestic violence leave are compensated by the increased work productivity, morale and stability.[16] This is an issue I will return to, as the impact on small businesses was the key point of contention in the Act.

Existing Domestic Violence Framework

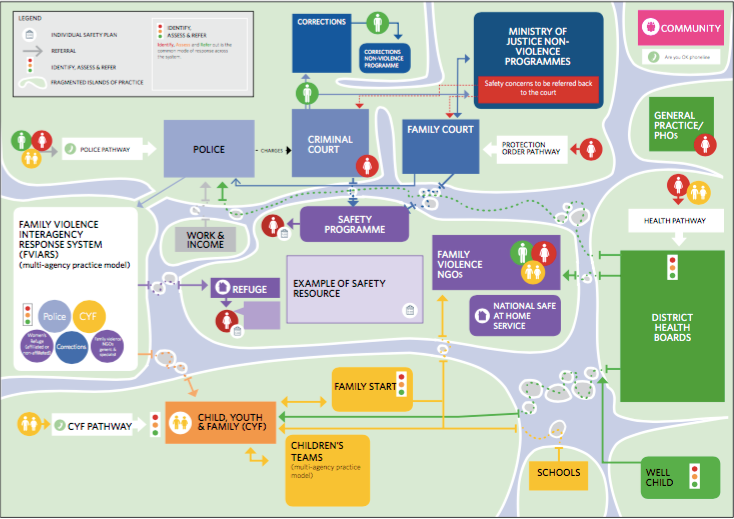

The Family Violence Death Review Committee describes New Zealand’s current domestic violence system as “a ‘system’ only by default rather than by design”.[17] They have helpfully compiled a diagram which documents how ‘helpful’ the support for domestic violence survivors is.[18] There are five different agencies involved, working with un-integrated policies and practices on different “islands”.[19]

The Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018 adds another “island” in the form of workplace safety. This is by no means a negative development, but it is another example of sporadic expansion of the support available for domestic violence survivors. Julia Tolmie comments that the system is complex and reforms must be systemic and participatory: “this is not a domain in which legislative reform alone will provide any kind of panacea”.[20] New Zealand needs cultural and systemic change to address domestic violence, although only time will tell whether this Act opens the door to substantive change or if it is merely another isolated support mechanism.

Application of the Act

First, it must be noted that many people affected by domestic violence are not employed. Further, many abusive partners encourage or force their partners to quit their jobs, or otherwise lose their jobs, out of fear of the financial independence and external support workplaces can provide.[21] Therefore, the application of the Act is already limited. Additionally, survivors may be reluctant to disclose their experiences of domestic violence to their employer where their employer knows the perpetrator or is generally unsympathetic.

A second issue is the long list of reasons an employer may reject a request for flexible working arrangements. The Act establishes that an employee’s request may be denied where it cannot be reasonably accommodated on one of eight grounds.[22] This section is intended to protect businesses, as the burden placed on small businesses in particular has been most frequently cited in criticism of the Act. However, some of the grounds are disconcertingly wide. For example, the grounds of inability to reorganise work among existing staff, detrimental impact on quality or performance, and/or detrimental effect on ability to meet customer demand could be applicable to any situation where there is one employee missing.[23]

A third possible issue is the potential requirement of proof of domestic violence. Namely, the Act does not elaborate what form the proof must take. A survivor will usually have nothing more than their testimony. Close attention must be placed on how employers utilise this requirement.

However, the Act has the potential to positively transform the lives of survivors of domestic violence. One survivor discussed how her employer’s support “saved [her] life” by putting security measures on her home and putting her in touch with a refuge, lawyers and police.[24] While this example goes beyond the expectations of the Act, it demonstrates just how far support outside the home can go. The Act is intended to establish a duty on employers to support employees; surely it is not too much to ask for an employer to care about their employee, beyond their productivity? The ability for a survivor to retain their employment and feel safe at work while making arrangements to escape or address domestic violence could be the difference between surviving an abusive relationship and becoming one of the 105,000 police call outs for domestic violence each year.[25]

Impact on Employers

A significant amount of research has been conducted on the impact of domestic violence leave on employers and businesses. The Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute noted in 2016 that the incremental wage pay-outs would be equivalent to 0.02 per cent of existing payrolls.[26] Additionally, those costs are likely to be “largely or completely” offset by the benefits of reduced turnover and increased productivity. A Canadian study revealed that 81.9% of people affected by domestic violence felt it negatively impacted their productivity, and domestic violence causes Canadian employers to lose $77.9 million annually.[27] Only 1.5 percent of female employees, and around 0.3 percent of male employees are likely to use their domestic violence leave in any given year;[28] in comparison, the average employee takes 4.7 days of sick leave each year.[29]

Several large employers already successfully operate domestic violence leave policies, such as The Warehouse Group, Countdown and ANZ.[30] The predominant fear inspired by this Act is that it will impact small business owners disproportionately – the “mum and dad who happen to have a dairy”, as suggested by National MP Judith Collins.[31] One solution to the potential cost for employers is getting government funding for domestic violence leave, although this would contradict the Act’s more community-orientated purpose as bestowing a duty on employers to support their employees.

Domestic violence is a systemic and historic national issue and the Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018 is only a drop in the ocean of domestic violence law reform. However, it attempts to empower survivors of domestic violence to retain their financial independence, which is a significant factor for escaping abusive relationships and cannot be understated. While the Act places the costs onto employers, the economic benefits of productivity have been demonstrated, and the moral duty to support employees is critical. The Act is starting a conversation about the extensive impact of domestic violence onto a survivor’s life, and hopefully this will be reflected in future holistic and systemic domestic violence law reform.

—The views expressed in the posts and comments of this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the Equal Justice Project. They should be understood as the personal opinions of the author. No information on this blog will be understood as official. The Equal Justice Project makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. The Equal Justice Project will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information nor for the availability of this information.

[1] (8 March 2017) 720 NZPD 16464-16465 per Jan Logie.

[2] Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Family Violence (OECD – Social Policy Division, 31 January 2013).

[3] Anna Leask “Family violence: 525,000 New Zealanders harmed every year” The New Zealand Herald (online ed, Auckland, 26 March 2017).

[4] Family Violence Death Review Committee Fifth Report: January 2014 to December 2015 (Health Quality & Safety Commission, February 2016) at 13.

[5] At 13.

[6] J Ptacek Battered Women in the Courtroom: The Power of Judicial Responses (Northeastern University Press, Boston, 1999).

[7] Family Violence Death Review Committee Fifth Report Data: January 2009 to December 2015 (Health Quality & Safety Commission, June 2017) at 12-13.

[8] Catriona MacLennan “Domestic violence: Why doesn't she leave?” The New Zealand Herald (online ed, Auckland, 7 April 2016).

[9] Above n 8.

[10] Laine Moger “Domestic violence bill: Survivor questions its practicality in the workplace” 17 August 2017 Stuff <www.stuff.co.nz>.

[11] Anna Aizer “The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence” (2010) 100 The American Economic Review 1847 at 1848.

[12] Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018, ss 6 and 31.

[13] Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018, s 6; and amended Employment Relations Act 2000, s 69ABEA.

[14] Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018, s 39; and amended Human Rights Act 1993, s 62A.

[15] Equal Justice Project “Submission to the Justice Committee on the Domestic Violence—Victims' Protection Bill” at 4.

[16] At 8.

[17] Family Violence Death Review Committee Fifth Report, above n 4, at 14.

[18] At 15.

[19] At 14.

[20] Julia R Tolmie (2018) “Coercive control: To criminalize or not to criminalize?” 18 Criminology & Criminal Justice 50 at 51.

[21] Moger, above n 10.

[22] Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018, s 6; and amended Employment Relations Act 2000, s 69ABF.

[23] Domestic Violence — Victims’ Protection Act 2018, s 6; and amended Employment Relations Act 2000, s 69ABF(2).

[24] Moger, above n 10.

[25] Leask, above n 3.

[26] Jim Stanford Economic Aspects of Paid Domestic Leave Provisions (Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute, December 2016) at 3.

[27] Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children Can Work be Safe, When Home Isn’t? Initial Findings of a Pan-Canadian Survey on Domestic Violence and the Workplace” (Learning to End Abuse, 2014).

[28] Stanford, above n 26, at 3.

[29] Stephen Summers Wellness in the Workplace: Survey Report 2015 (Southern Cross Health Society and Business NZ, 2015) at 9

[30] Lucy Bennett “Bill allowing leave for domestic violence victims passes third reading” The New Zealand Herald (online ed, Auckland, 25 July 2018).

[31] (25 July 2018) 731 NZPD 5287.