Cross-Examination: New Zealand's Child Poverty Problem

Ari Apa, content contributor

In 1978 New Zealand signed up to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC), which requires the State to protect children’s rights to social security and standards of living adequate for their mental, spiritual, moral and social development.[1] This is a binding legal obligation, which not only guarantees the provision of adequate standards of living, but the continuous improvement of living conditions for children. So why it is that by some measures, twenty-five percent of children in New Zealand are regarded as currently living in poverty?[2] Why is it that children still get sick, and even die because of the inadequate quality of housing provided by our State? Tackling this issue through specific child poverty legislation is a step worth taking if the New Zealand government is to fulfill its obligations to Kiwi kids. Child deprivation rates in New Zealand are higher than in most Western European countries, and in a recent study our country was ranked 20th out of 35 developed countries.[3] Societies pay a heavy price for failing to protect its children from poverty: lower returns on educational investments, reduced skills and productivity, increased likelihood of unemployment and welfare dependence, and higher costs of social protection and judicial systems.[4] Therefore States are not only morally and legally obliged to protect children from falling into poverty, but there is also an economic incentive for doing so. One way of achieving this is by introducing specific legislation which provides an enduring policy framework for reducing and eradicating child poverty.The New Zealand government has been criticized for not doing its utmost to address child poverty.[5] This was demonstrated in June 2014 at the Universal Periodic Review process at the United Nations Human Rights Council, where our government rejected 34 of the recommendations made by other States, including specific advice on strengthening New Zealand’s legal protection of economic, social and cultural rights that would guide genuine solutions to addressing its poor performance on issues such as child poverty.[6] The current legislative context in New Zealand demonstrates “an absence of any direct intent on the part of the legislature to define or reduce child poverty.”[7] The main statutes concerned with public expenditure and social security (the Public Finance Act 1989 and the Social Security Act 1964) do not contain any statutory principles or objectives that give consideration to child poverty, or any analogous concept. The first time direct reference has been made to the social and economic wellbeing of children was in The Vulnerable Children’s Act 2014, which is a legislation designed address violence against children, and includes specific reference to “improving the social and economic well-being” of vulnerable children.[8] However, what New Zealand lacks is a specific policy strategy to reduce child poverty, or a statutory framework upon which such a strategy can be based.[9]Child Poverty Legislation? Implementing legislation, which makes specific and direct reference to the social and economic wellbeing of children, may be key to driving down child poverty rates in New Zealand. Lessons from the UK’s child poverty legislation give us an insight into what legislation of this kind should include and how it should go about meeting targets for reducing child poverty.[10] Specifically, New Zealand’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty (EAG) has recommended that such legislation would achieve the following things:[11]

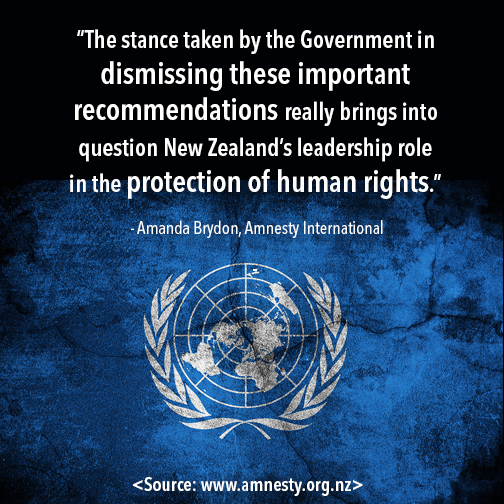

Child deprivation rates in New Zealand are higher than in most Western European countries, and in a recent study our country was ranked 20th out of 35 developed countries.[3] Societies pay a heavy price for failing to protect its children from poverty: lower returns on educational investments, reduced skills and productivity, increased likelihood of unemployment and welfare dependence, and higher costs of social protection and judicial systems.[4] Therefore States are not only morally and legally obliged to protect children from falling into poverty, but there is also an economic incentive for doing so. One way of achieving this is by introducing specific legislation which provides an enduring policy framework for reducing and eradicating child poverty.The New Zealand government has been criticized for not doing its utmost to address child poverty.[5] This was demonstrated in June 2014 at the Universal Periodic Review process at the United Nations Human Rights Council, where our government rejected 34 of the recommendations made by other States, including specific advice on strengthening New Zealand’s legal protection of economic, social and cultural rights that would guide genuine solutions to addressing its poor performance on issues such as child poverty.[6] The current legislative context in New Zealand demonstrates “an absence of any direct intent on the part of the legislature to define or reduce child poverty.”[7] The main statutes concerned with public expenditure and social security (the Public Finance Act 1989 and the Social Security Act 1964) do not contain any statutory principles or objectives that give consideration to child poverty, or any analogous concept. The first time direct reference has been made to the social and economic wellbeing of children was in The Vulnerable Children’s Act 2014, which is a legislation designed address violence against children, and includes specific reference to “improving the social and economic well-being” of vulnerable children.[8] However, what New Zealand lacks is a specific policy strategy to reduce child poverty, or a statutory framework upon which such a strategy can be based.[9]Child Poverty Legislation? Implementing legislation, which makes specific and direct reference to the social and economic wellbeing of children, may be key to driving down child poverty rates in New Zealand. Lessons from the UK’s child poverty legislation give us an insight into what legislation of this kind should include and how it should go about meeting targets for reducing child poverty.[10] Specifically, New Zealand’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty (EAG) has recommended that such legislation would achieve the following things:[11]

- Entrenchment of a systematic approach to child poverty policy development across the layers of government.

- A statutory status. The targets of the Act would subject the government to a much higher degree of public scrutiny.

- A mechanism that expressly links budgetary processes and other fiscal planning and decision-making processes. This would make it possible to track whether fiscal choices made by the government are being made in a manner consistent with the statutory objectives of the Child Poverty legislation.

- Barriers and limitations to progress are more readily identified and addressed with the implementation of statutory status.

A private member’s bill, designed along the lines of the EAG’s legislative model, was recently introduced by Jacinda Ardern. Importantly, the bill provides a statutory definition of child poverty which is important for the way our anti-poverty policy is shaped.[12] The Importance of Housing Policy The quality and affordability of housing was seen as the most important action to mitigate the effects of child poverty, according to an EAG report.[13] Therefore, any policy framework for reducing child poverty should prioritise housing policy. This is an area which has gained much publicity in New Zealand after the death of two-year-old Emma-Lita Bourne last year. Bourne’s death was the result of pneumonia, partly attributable to the cold and damp conditions of the State house she lived in.[14]The family was given a heater, but they could not afford the electricity to run it. As Kris Gledhill accurately points out, governments are responsible for ensuring homes are safe for its citizens, especially children; article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (to which NZ is a party) states that everyone has the right to an adequate standard of living. [15] Not only that, but the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act guarantees the right to life, a right which obliges the government to take steps wherever it is aware that death is risked and can be avoided. [16] It is well known that living in a cold, damp house will have adverse or even life-threatening effects on health. Professor Philippa Howden-Chapman, director of the Housing and Health Research Programme at Otago University, says that 40,000 child hospital admissions each year are for respiratory conditions to which poor housing has contributed.[17] Home is where children should feel the most safe and secure, so our government’s efforts to reduce and eradicate child poverty in New Zealand should begin by ensuring children have safe, warm homes. The Healthy Homes Guarantee Bill was introduced by Phil Twyford in late 2013, which would have introduced requirements that all rental housing (State, social and private) meet minimum health and safety standards in regard to insulation and heating. [18] However, the bill failed at the first reading.Surveys and submissions used for an EAG report showed strong support for the enactment of legislation to formalize the setting of targets to reduce child poverty, monitor progress and report results.[19] Enactment of legislation specifically addressing child poverty will ensure public visibility and governmental accountability, without which the issue is liable to falling off the political and media agenda.[20] The issue of safe housing for children is an important aspect of reducing child poverty in New Zealand, with so many children suffering respiratory illnesses because of damp and cold homes our Government should be called to account.

The Importance of Housing Policy The quality and affordability of housing was seen as the most important action to mitigate the effects of child poverty, according to an EAG report.[13] Therefore, any policy framework for reducing child poverty should prioritise housing policy. This is an area which has gained much publicity in New Zealand after the death of two-year-old Emma-Lita Bourne last year. Bourne’s death was the result of pneumonia, partly attributable to the cold and damp conditions of the State house she lived in.[14]The family was given a heater, but they could not afford the electricity to run it. As Kris Gledhill accurately points out, governments are responsible for ensuring homes are safe for its citizens, especially children; article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (to which NZ is a party) states that everyone has the right to an adequate standard of living. [15] Not only that, but the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act guarantees the right to life, a right which obliges the government to take steps wherever it is aware that death is risked and can be avoided. [16] It is well known that living in a cold, damp house will have adverse or even life-threatening effects on health. Professor Philippa Howden-Chapman, director of the Housing and Health Research Programme at Otago University, says that 40,000 child hospital admissions each year are for respiratory conditions to which poor housing has contributed.[17] Home is where children should feel the most safe and secure, so our government’s efforts to reduce and eradicate child poverty in New Zealand should begin by ensuring children have safe, warm homes. The Healthy Homes Guarantee Bill was introduced by Phil Twyford in late 2013, which would have introduced requirements that all rental housing (State, social and private) meet minimum health and safety standards in regard to insulation and heating. [18] However, the bill failed at the first reading.Surveys and submissions used for an EAG report showed strong support for the enactment of legislation to formalize the setting of targets to reduce child poverty, monitor progress and report results.[19] Enactment of legislation specifically addressing child poverty will ensure public visibility and governmental accountability, without which the issue is liable to falling off the political and media agenda.[20] The issue of safe housing for children is an important aspect of reducing child poverty in New Zealand, with so many children suffering respiratory illnesses because of damp and cold homes our Government should be called to account.

---

[1] United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC) 1577 UNTS 3(entered into force 2 September 1990), arts 26 and 27.[2] Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty Solutions to Child Poverty in New Zealand: Evidence for Action (Children’s Commissioner, 2012) at 5.[3] At 11.[4] At 14–17.[5] “New Zealand rejects recommendations to address inequality” (20 June 2014) Amnesty International New Zealand <www.amnesty.org.nz>.[6] Amnesty International New Zealand, above n 5.[7] John Hancock Legislating to Reduce Child Poverty (Department of Internal Affairs, 2014) at 24.[8] The Vulnerable Children Act 2014, s 6.[9] Hancock, above n 7, at 29.[10] Child Poverty Act 2010 (UK).[11] Hancock, above n 7, at 29.[12] Child Poverty Reduction and Eradication Bill 2014 (Member’s proposal).[13] Hancock, above n 7, at 47 and 20.[14] Corazon Miller “Damp house led to toddler's death” The New Zealand Herald (online ed, New Zealand, 4 June 2015).[15] Kris Gledhill "The Responsibilities of Governments" (14 June 2015) The Standard <thestandard.org.nz>; Universal Declaration of Human Rights GA Res 217A, III (1948); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 993 UNTS 3 (opened for signature 19 December 1966, entered into force 3 January 1976).[16] The Bill of Rights Act 1990, s 8.[17] Peter Calder “Cold, harsh truth for so many kids” The New Zealand Herald (online ed, New Zealand, 10 June 2015).[18] Healthy Homes Guarantee Bill 2013 (164-1).[19] Hancock, above n 7, at 16.[20] Mark Henaghan “Why We Need Legislation to Address Child Poverty” (2013) 9 Policy Quarterly 30 at 33.

---

The views expressed in the posts and comments of this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the Equal Justice Project. They should be understood as the personal opinions of the author. No information on this blog will be understood as official. The Equal Justice Project makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. The Equal Justice Project will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information nor for the availability of this information.

[x_share title="Share this Post" facebook="true" twitter="true"]