Cross-Examination: The Right to Die in New Zealand

Pooja Upadhyay

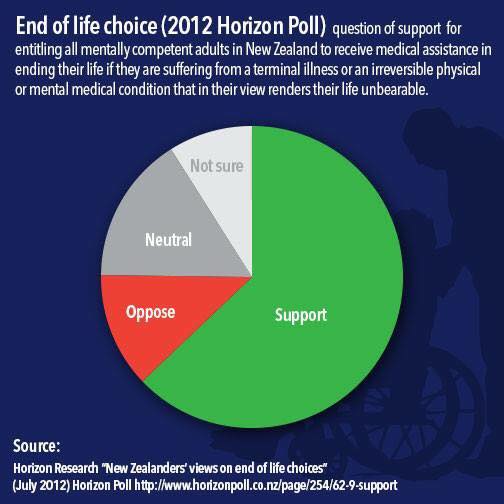

Our right to life is enshrined in the fabric of New Zealand society through legislation such as the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990.[1] However, our right to death can be seen as non-existent or inaccessible to all. The autonomy to choose when and how to die when suffering intolerably from a terminal disease is not granted to the people who may arguably need such a right the most — people like Lecretia Seales who is suffering from brain cancer.[2]The Crimes Act 1961 criminalises both the aiding and abetting of suicide under s 179 and disallows people to give consent to an infliction of death upon oneself in s 63.[3] These seem to be the biggest legal barriers between Ms Seales and her right to assisted suicide. Ms Seales’ plea for the law to grant everyone with what she claims is a “fundamental human right” has brought this contentious and deeply sensitive issue to the public sphere once again.[4]Advocates of assisted suicide may have a strong argument in saying the right to choose one’s time of death is in fact a fundamental human right. First, Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides human beings with a right to his or her own “life” and “liberty”.[5] First, the right to life could be assumed as the implied right to end that life - ‘the right to death’. Likewise, liberty can be extended to the freedom of one to act on their body as they wish, including bodily self-harm resulting in death. Additionally the Crimes Act 1961 does not actively criminalize suicide or self-murder.However, the absence of the express criminalisation of self-exercised suicide may not necessarily insinuate a right to it. As posited by Lord Hope, the decriminalisation of self-murder within the United Kingdom Suicide Act 1961 “did not create a right to commit suicide.”[6] Instead, the “sanctity of human life” is “probably the most fundamental of the human social value”, whose worth is “recognised in all civilised society and their legal systems”.[7] This is evinced by the criminal consequences imposed on offenders who threaten and disrupt such sanctity.[8]Nevertheless, if an active ‘right’ to end one's own life exists in the law, the rule of law holds that we are all equal before it and should be granted it regardless of our physical incapacities.[9] However, due to the prohibition of assisted suicide, people who are physically challenged and depend on the assistance of others to exercise their right to suicide are robbed of it. In light of this, the law favours the physically competent and disadvantages the physically disabled. Thereupon we may conclude that this law is discriminatory.Conversely, this rule of law argument is weakened when applied to the legalization of assisted suicide as opposed to its prohibition. If such a law were to exist, presumably safeguards would be implemented, specifying who is granted the right to assistance and who is not. Mental incompetency for example is often a ground on which requests for assisted suicide are rejected.[10] In this way, the legalization of right to assisted suicide could also be deemed discriminatory.Discrimination on such grounds is unsuited to New Zealand’s egalitarian constitutional and legal values. Protective legislation against discrimination include The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 in s 19 and the Human Rights Act 1993 which specifically outlines disability as a prohibited ground of discrimination.[12] Are we comfortable with accepting and enforcing a law that deprives people of a fundamental human right? Conversely, are we comfortable with the discrimination that comes with the granting of assisted suicide?New Zealanders certainly expect the government to meet standards of equality and many believe that the prohibition on assisted suicide protects our right to life rather than deprives us of potential extensions of this right (such as the right to death).[13] This is the primary justification for the prohibition in many jurisdictions such as our own.[14] The prohibition protects against the “slippery-slope” argument that refers to the dangers of abuse that may occur should assisted suicide be made legal.[15]Specifically, the prohibition protects “decisionally vulnerable” patients.[16] What is meant by this is that the consent by the patient for their assisted death may not be their true and rational choice. Such consent could occur notwithstanding that the victim’s consensual application was correctly administered. This may occur when vulnerable members of society are manipulated, coerced or become subject to mental illness to such an extent that they think of themselves as a burden on their families and that suicide is truly the best option for them.[17] Alternatively, in cases of homicide, the offender may claim that they their victim consented to the killing when the victim was actually ‘decisionally vulnerable’ and so killed without true consent. As it can be seen, the right to assisted suicide may be abused and safeguards to prevent these abuses have been seen as unworkable.[18] Given such reasons, the prohibition can be deemed vital.This brings forward another contentious and significant question between values and policy.[19] How much should we value personal autonomy over the risk to the physically and mentally vulnerable?In some jurisdictions, personal autonomy considerations prevail. A representation of Canada’s stance can be taken from Carter v Canada, where the benefits of such laws were not worth the limitations imposed on rights as a result.[20] The argued benefit was the protection of the vulnerable.[21] The argued cost was the deprivation of principles of fundamental justice, regarding the ability to choose how and when to die.[22] The judges from the Supreme Court of Canada do not stand alone in this view, as many jurisdictions such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg have legalised variations of assisted suicide within the past few decades.[23] Some safeguards put in place in the said jurisdictions include the involvement of two health professionals who must be satisfied that the patient is well informed and has voluntarily consented.[24]Research on the operation of the Netherlands' Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act concluded that abuses were not extensive.[25] Around 80 per cent of euthanasia and assisted suicide cases were reported – leaving majority of euthanasia cases in the safety of the protections outlined in the law.[26] Although the unreported cases are luckily of a minority, we cannot simply quantify the value of life and assess this as an acceptable statistic. It is still a concern that 20 per cent of cases are unaccounted for. In light of this, the successfulness of the operation of the law is highly debated.As a contrast to the Netherlands, the punitive position of New Zealand law on assisted suicide demonstrates that the risks to the vulnerable outweigh the importance of providing assisted suicide rights to individuals. The law is supported by organisations such as The Care Alliance and specifically Euthanasia-Free NZ, who protest that, “[l]egal assisted suicide is too dangerous for society”.[27]However, New Zealanders have taken steps to bring this issue before the House of Representatives. One example is the Death with Dignity Bill 2003 that was struck down by the House at first reading.[28] A more recent example is Maryan Street’s End of Life Choice Bill 2012 that allowed people with particular circumstances to seek medically assisted suicide.[29] Those that would have qualified within Street’s bill include:[30]

- New Zealand citizens that are;

- 18 years and older who;

- Suffer from a terminal illness that could end their lives within 12 months or;

- Suffer from an irreversible physical or mental condition that in the person’s view renders their life as unbearable as long as they are;

- Mentally competent.

The last point is controversial in light of the aforementioned rule of law argument, as the right to assisted suicide would not be extended to the mentally incompetent. The bill tries to clarify what is meant by mentally competent as follows:[31]

5 Meaning of mentally competent(1) For the purposes of this Act, a person is mentally competent if he or she has the ability to understand the nature and consequences of a request to end his or her life, in the knowledge that the request will be put into effect; and mentally incompetent has a corresponding meaning.(2) A person is presumed to be mentally competent unless the contrary is shown.

This generates a debate on the fairness of such a requirement as well as how well we can determine what true mental incompetency is. Nevertheless, the safeguards outlined in the bill include a “right not to participate”[32] and a confirmation by medical practitioner that nobody involved in the end of life procedure has been coerced into it.[33] A review body would be established to regularly assess the operation of the procedures.[34]However, Street’s bill did not complete its journey to the House as it was withdrawn in 2013 on the grounds that MPs were likely vote against the bill in an election year.[35] This could mean that the issue is too controversial for politicians and the current government to take on, or that there is perhaps not enough popular support to mobilize change. Confusingly, a Horizon poll (results shown above) in 2012 concluded that 70 per cent of National Party voters were in favour of allowing adults to undergo medically assisted suicide.[36] Additionally, there was an overall majority in favour of the right.[37] Ms Seales’ story has been received through many platforms such as the New Zealand Herald, Radio NZ and the Listener. A community page on Facebook called “Lecretia’s Choice” has almost 2000 supporters. Public engagement seems to be far from insignificant.Should the law remain, people in circumstances such as Ms Seales’ have the option to submit to starvation, undergo a violent death or reject medical treatment.[38] The latter option allows for a medical practitioner to omit from providing the patient with treatment until eventual death - the doctor’s omission being indirect assistance to this drawn out suicide. Similarly, the law permits a doctor to accelerate a person’s death through omission (with judicial approval) where proper medical practice holds that it is in the patient’s best interest to withdraw treatment without their express consent.[39] The double effect doctrine morally justifies this, as the intention to alleviate the patient’s suffering was ethical and good.[40] Consequently, the law can be deemed hypocritical as it permits doctors to essentially aid death through omission whilst assisted suicide and euthanasia still remain illegal.[41]Regardless, aside from the options above, patients can take support from the palliative care resources in New Zealand. The Ministry of Health has given attention to the improvement of palliative care relatively recently, through the New Zealand Palliative Care Strategy of 2001.[42] Organizations such as Hospice New Zealand whose vision is to give people the “opportunity to celebrate their life” provide a respectful and caring environment in which the terminally ill can live.[43]Lecretia Seales knows she may not live to see her goals realized.[44] Nevertheless, she remains focused on her journey towards legalising the right to decide how and when she will pass away through a “Right to Die” petition for the High Court.[45] It will be a great source of legal and public interest to see how this issue progresses.

Confusingly, a Horizon poll (results shown above) in 2012 concluded that 70 per cent of National Party voters were in favour of allowing adults to undergo medically assisted suicide.[36] Additionally, there was an overall majority in favour of the right.[37] Ms Seales’ story has been received through many platforms such as the New Zealand Herald, Radio NZ and the Listener. A community page on Facebook called “Lecretia’s Choice” has almost 2000 supporters. Public engagement seems to be far from insignificant.Should the law remain, people in circumstances such as Ms Seales’ have the option to submit to starvation, undergo a violent death or reject medical treatment.[38] The latter option allows for a medical practitioner to omit from providing the patient with treatment until eventual death - the doctor’s omission being indirect assistance to this drawn out suicide. Similarly, the law permits a doctor to accelerate a person’s death through omission (with judicial approval) where proper medical practice holds that it is in the patient’s best interest to withdraw treatment without their express consent.[39] The double effect doctrine morally justifies this, as the intention to alleviate the patient’s suffering was ethical and good.[40] Consequently, the law can be deemed hypocritical as it permits doctors to essentially aid death through omission whilst assisted suicide and euthanasia still remain illegal.[41]Regardless, aside from the options above, patients can take support from the palliative care resources in New Zealand. The Ministry of Health has given attention to the improvement of palliative care relatively recently, through the New Zealand Palliative Care Strategy of 2001.[42] Organizations such as Hospice New Zealand whose vision is to give people the “opportunity to celebrate their life” provide a respectful and caring environment in which the terminally ill can live.[43]Lecretia Seales knows she may not live to see her goals realized.[44] Nevertheless, she remains focused on her journey towards legalising the right to decide how and when she will pass away through a “Right to Die” petition for the High Court.[45] It will be a great source of legal and public interest to see how this issue progresses.

---

[1] New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, s 8.[2] Rebecca Macfie “Dying wishes” New Zealand Listener (online ed, New Zealand, 8 January 2015).[3] The Crimes Act 1961, ss 179 and 63.[4] Macfie, above n 2.[5] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art 3.[6] R (Pretty) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2001] UKHL 61, [2002] 1 AC 800 at [106].[7] At [109].[8] R (Nicklinson) v Ministry of Justice [2014] UKSC 38, [2014] 3 WLR 200 at [209].[9] Duncan Webb, Katherine Sanders and Paul Scott The New Zealand Legal System: Structures and Processes (5th ed, LexisNexis, Wellington, 2010) at 3.3(d).[10] Ben While and Lindy Willmott “Proposed Legal Frameworks for Assisted Dying in Canada: How Do They Compare to Legislation Abroad?” (December 2014) Dying With Dignity Canada .[11] Matthew SR Palmer “New Zealand Constitutional Culture” (2007) 22 NZULR 561 at 578.[12] Human Rights Act 1993 (NZ), s 21(h).[13] Palmer, above n 10, at 575.[14] Pretty v The United Kingdom [2002] 35 EHRR 1 at 74.[15] Robert M Walker “Physician-Assisted Suicide: The Legal Slippery Slope” (2001) 8 Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center 25 at 26.[16] Carter v Canada (Attorney General) [2015] SCC 5 at [114].[17] At [114].[18] R (Pretty) v Director of Public Prosecutions, above n 6, at [54].[19] R (Nicklinson) v Ministry of Justice, above n 8, at [229].[20] Carter v Canada (Attorney General), above n 16.[21] At [29].[22] At [31].[23] While and Willmott, above n 9.[24] While and Willmott, above n 9.[25] While and Willmott, above n 9.[26] Bregje D Onwuteaka-Philipsen and others “Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey” (2012) 380 The Lancet 908.[27] “Legalising Assisted Suicide is Dangerous!” (2015) Euthanasia-Free NZ <http://euthanasiadebate.org.nz/>.[28] (30 July 2003) 610 NZPD 7425.[29] Macfie, above n 2.[30] End of Life Choice Bill 2012, s 4.[31] Section 5.[32] Section 27.[33] End of Life Choice Bill 2012.[34] Section 35.[35] Macfie, above n 2.[36] Horizon Research “New Zealanders’ views on end of life choices” (July 2012) Horizon Poll < www.horizonpoll.co.nz>.[37] Horizon Research.[38] The Bill of Rights Act 1990, s 11.[39] AP Simester and WJ Brookbanks Principles of Criminal Law (4th ed, Brookers, Wellington, 2012) at 50.[40] “The doctrine of double effect” (2014) BBC .[41] Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] 2 WLR 316 (HL).[42] “The New Zealand Palliative Care Strategy” (2 February 2001) Ministry of Health <http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-palliative-care-strategy>.[43] “Vision & Values” (2015) Hospice New Zealand <http://www.hospice.org.nz/about-hospice-nz/vision-amp-values>.[44] Macfie, above n 2.[45] “Restrictions on Right to Die interventions accepted” (28 April 2015) my.lawsociety <http://my.lawsociety.org.nz/>.The views expressed in the posts and comments of this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the Equal Justice Project. They should be understood as the personal opinions of the author. No information on this blog will be understood as official. The Equal Justice Project makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. The Equal Justice Project will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information nor for the availability of this information.